The code compiles. All the tests pass. The staging environment is healthy. Yet once per day a few servers in the production fleet mysteriously observe a crash with an error message that makes no sense – unreachable code has been reached, we have taken 9 items out of a collection that can only hold 8, or similar. Welcome to the world of rolling your own synchronization primitives.

Even after twenty years in the code mines, encountering custom thread synchronization logic brings fear and doubt into the head of the author. It is so easy to make a mistake and so hard to notice it.

Importantly, in today’s AI-enriched engineering loop, we may find ourselves incorporating custom synchronization logic without always realizing it! Anecdotal evidence suggests that LLMs are quite content to use atomic variables for custom multithreaded signaling and synchronization logic even when safer alternatives like mutexes or messaging channels are available.

While a thorough treatment of logic synchronization would be an entire book, this article aims to paint a picture of some of the basics of custom synchronization primitives, providing readers with an approachable treatment of some essential knowledge that may help them at least review and validate such logic when generated by AI coding assistants.

There are two key construction materials used to create synchronization primitives:

- Atomic variables – these are variables imbued with special properties by both the compiler and the hardware architecture. Operating on atomic variables is innately tied to memory ordering constraints which are the true mechanism by which logic on different threads is synchronized.

- Specialized operating system API calls – specialized operations like “suspend this thread until XYZ happens”, typically used when one thread needs to wait for an event that occurs on another thread.

This article will only look at the former, exploring some usages of atomic variables and the fundamental logic synchronization capabilities they offer in situations where we deliberately avoid using higher-level synchronization primitives. We explore some common pitfalls and see how we can avoid them by applying relevant verification tooling and by following some key design principles.

The name “atomic variables” is incredibly misleading, as it over-emphasizes the atomicity properties of these variables. While these properties do exist and are relevant to this topic, atomic variables might better be thought of as “thread-aware variables” because they also have other properties that are just as important as atomicity. This unfortunate naming bias has likely contributed to the topic being as difficult to comprehend as history has proven it to be – many of the reasons we use atomic variables are not (only) because they are atomic!

In particular, we will try to distinguish the atomicity and memory ordering properties of atomic variables very clearly in this article. We start with the classic multithreading example of trying to increment a counter on two threads.

Note: the code snippets in this article are extracts that showcase only the essentials. The complete repository is available at https://github.com/sandersaares/order-in-memory.

A failure to increment

Two threads are working on shared data and due to a programming mistake the program ends up with the wrong result. Let’s examine what happens, why it happens and how to fix it.

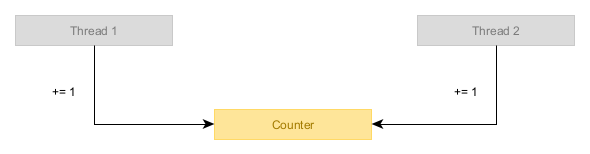

Our program consists of two threads that will be incrementing the same counter.

Each thread increments the counter 1 million times, so we expect our program to end up with a value of 2 million in the counter.

const INCREMENT_COUNT: u64 = 1_000_000;fn main() { static mut COUNTER: u64 = 0; let thread_a = thread::spawn(|| { for _ in 0..INCREMENT_COUNT { _ = black_box(unsafe { COUNTER += 1; }); } }); let thread_b = thread::spawn(|| { for _ in 0..INCREMENT_COUNT { _ = black_box(unsafe { COUNTER += 1; }); } }); thread_a.join().unwrap(); thread_b.join().unwrap(); assert_eq!(unsafe { COUNTER }, INCREMENT_COUNT * 2); println!("All increments were correctly applied.");}Note the usage of

black_box()inside the loops. This is important to avoid the compiler optimizing away the entire loop into a “+= 1_000_000”. The black box creates an optimization barrier between the increment and the loop. The code we write is not always going to match the code that the hardware executes. Understanding the allowed compiler transformations can be crucial for creating valid multithreaded code using low-level primitives.

Note also the usage of

unsafeblocks. The Rust programming language tries to protect us from shooting ourselves in the foot here and refuses to allow this incorrect multithreaded logic to be written in its default safe mode. Unsafe does not mean invalid – switching Rust to unsafe mode simply means the programmer takes over some of the responsibilities of the compiler. In this case, however, it does mean invalid – we will intentionally fail to fulfill our responsibilities for example purposes.

Running this code will give different answers from run to run but almost always, the answer will be an assertion failure because the counter did not reach the expected value of 2 million.

cargo run --example 01_failure_to_increment --release --quiet

thread 'main' (34824) panicked at examples\01_failure_to_increment.rs:27:5:

assertion left == right failed

left: 1105737

right: 2000000

If you have access to systems on different hardware platforms, try this code on both Intel/AMD and ARM processors (e.g. a Mac). You may find the results differ in interesting ways. If you spot such a difference, leave a comment with your best guess as to why it exists.

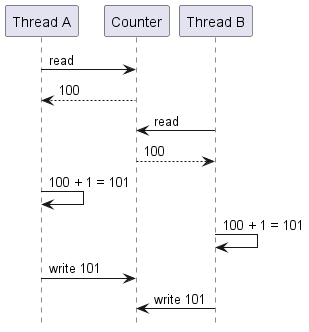

The simple story with this example is that each loop iteration consists of:

- Loading the current value from the variable.

- Incrementing it.

- Storing the new value back in the variable.

This immediately suggests some ways for the two threads to interfere with each other.

The two threads might both load the same value, increment it by one, and simultaneously (or near enough) store the new value. Logically speaking, two increments happened, but the value only changed by 1.

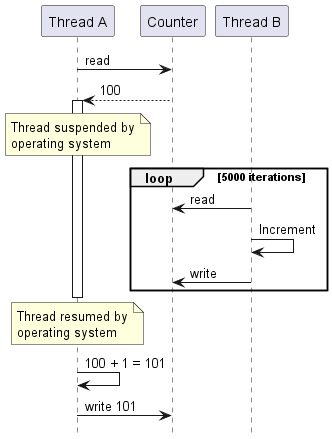

Alternatively, a thread might load the value N, then be suspended by the operating system, then after the other thread has done 5000 increments to reach N+5000, then the original thread resumes executing and writes N+1, erasing 5000 increments made by the other thread.

This is a data race, which is considered undefined behavior in Rust. This program is invalid.

The fix is simple: we must tell the compiler that this counter is being accessed from multiple threads simultaneously. This is what atomic variables can fix – their atomicity property guarantees that any operation performed on an atomic variable will have the same effect no matter how many threads are accessing it simultaneously. We need to use atomic variables whenever some data is accessed by multiple threads concurrently and at least one of those threads is writing to it.

To apply this fix, we change our counter from u64 to AtomicU64. Instead of += to increment, we change to use fetch_add(). This method also requires an argument to specify the memory ordering constraints to apply for this operation. In context of this example, we just specify Relaxed ordering, which means “no constraints” and gives the compiler and the hardware maximum flexibility in how they are allowed to compile and execute this operation.

const INCREMENT_COUNT: u64 = 1_000_000;fn main() { static COUNTER: AtomicU64 = AtomicU64::new(0); let thread_a = thread::spawn(|| { for _ in 0..INCREMENT_COUNT { _ = black_box(COUNTER.fetch_add(1, Ordering::Relaxed)); } }); let thread_b = thread::spawn(|| { for _ in 0..INCREMENT_COUNT { _ = black_box(COUNTER.fetch_add(1, Ordering::Relaxed)); } }); thread_a.join().unwrap(); thread_b.join().unwrap(); assert_eq!(COUNTER.load(Ordering::Relaxed), INCREMENT_COUNT * 2); println!("All increments were correctly applied.");}We no longer need to use the unsafe keyword here, which is good because it is not possible to have data races in safe Rust code. Note that it is still possible to have logic errors (including synchronization logic errors) in safe Rust code – “safe” does not mean “correct”. Still, by getting rid of the unsafe keyword, an entire class of potential errors has been eliminated, so it is a very desirable change.

Running the program, we now see what we expect to see – the counter is always incremented by two million:

cargo run --example 02_failure_to_increment_fixed --release --quiet

All increments were correctly applied.

The point of this first example was to highlight the atomicity property of atomic variables, which enables multiple threads to operate on the same variable as if the operations on that variable were happening on a single thread.

The key part of that phrase is “on that variable”! Atomicity is not enough if we have more than one variable we need to work with! That’s where memory ordering constraints come into the picture, right after a brief detour.

Sidequest: detecting data races

If we never use the unsafe keyword, we can be certain that there are no data races in our Rust code, as that is one of the promises of safe Rust. However, what if we do use unsafe code? The unsafe keyword is a legitimate Rust feature and merely lowers the guardrails, enabling us to write code that we believe is perfectly valid but which simply cannot be fully verified by the compiler.

That “we believe” is a problem! If we make a mistake in low-level synchronization logic, we may not find out for years. We might only observe that 10 times per day, a random server out of our fleet of 10 000 experiences a bizarre crash whose crash dump makes no sense, taking down thousands of real user sessions without anyone being able to reproduce it in the lab. Such failures are not merely theoretical – those 10 000 servers were very real and the author has gone through exactly such a months-long detective adventure.

The good news is that Rust offers a helping hand here. The Rust toolchain includes the Miri analysis tool, which is capable of detecting data races and other kinds of invalid code. Use it as a wrapper around your “run” or “test” Cargo commands. For example, to run the first example under Miri:

rustup toolchain install nightly

rustup +nightly component add miri

cargo +nightly miri run --example 01_failure_to_increment

error: Undefined Behavior: Data race detected between (1) non-atomic write on thread `unnamed-1` and (2) non-atomic read on thread `unnamed-2` at alloc1

--> examples\01_failure_to_increment.rs:19:17

|

19 | COUNTER += 1;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^ (2) just happened here

|

help: and (1) occurred earlier here

--> examples\01_failure_to_increment.rs:11:17

|

11 | COUNTER += 1;

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^

= help: this indicates a bug in the program: it performed an invalid operation, and caused Undefined Behavior

= help: see https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/reference/behavior-considered-undefined.html for further information

= note: this is on thread `unnamed-2`

note: the current function got called indirectly due to this code

--> examples\01_failure_to_increment.rs:16:20

|

16 | let thread_b = thread::spawn(|| {

| ____________________^

17 | | for _ in 0..INCREMENT_COUNT {

18 | | _ = black_box(unsafe {

19 | | COUNTER += 1;

... |

22 | | });

| |______^

Miri will immediately complain about any data race it sees. Its detections rely on our examples/tests actually executing a problematic sequence of operations, which is not always easy to organize but for anything with test/example coverage, it is an invaluable validation tool.

Testing with Miri should be considered mandatory for any code that contains the keyword unsafe.

Miri is also strongly recommended for testing safe code that directly uses 3rd party crates that rely on unsafe code, as an additional safety net on top of the 3rd party crate’s own tests. Validating even safe code under Miri has proven its value to the author by revealing issues in 3rd party crates, even popular crates that one might expect to already be fully tested and battle-proven.

While Miri can run both stand-alone binaries and tests, using it does require some special attention. This is because Miri is best thought of as something similar to emulator, perhaps as even as a separate operating system and hardware platform. The challenge is that this emulated platform does not have a real Windows, Linux or Mac operating system running on it – if the app tries to talk to the operating system, it will simply panic. While some operating system APIs are emulated, the majority are not. Trying to perform network communications or spawn additional processes is not going to work under Miri, for example.

This generally means that only a subset of tests can be executed under Miri, with the others having to be excluded via #[cfg_attr(miri, ignore)].

There is no easy solution to that limitation – to benefit from Miri, we must design our APIs so that the logic containing unsafe blocks is completely separate from logic that talks to operating system APIs Miri does not emulate.

Having completed our sidequest and learned how to use Miri for detecting data races, let’s return to exploring the second important property of atomic variables – the ability to define memory ordering constraints.

And then there were two variables

Recall that the atomicity property of atomic variables is sufficient for correctness only if we need to work with a single variable. The next example scenario introduces two separate variables: an array and a pointer to this array. To synchronize this example correctly we will need to introduce memory ordering constraints.

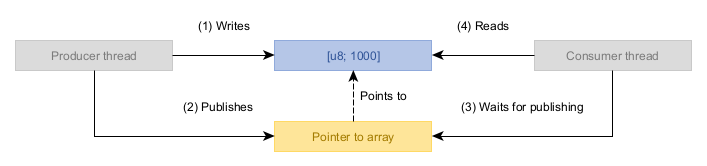

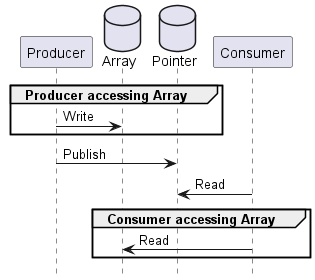

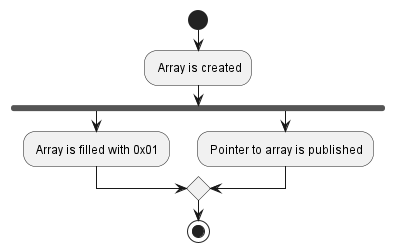

The logic of this example is relatively straightforward. We have two threads: Producer and Consumer. Producer delivers some data to Consumer. The workload consists of the following conceptual operations:

- Producer creates an array of 1000 bytes, writing the value

0x01into each byte. In other words, it creates the equivalent of a[1_u8; 1000]. - Once the array has been created and filled, Producer publishes a pointer to this array via a shared variable (which contains a null pointer until the array gets published).

- Consumer waits for this pointer to become non-null, indicating Producer has published the array.

- Consumer sums the values of all the bytes in the array, expecting to see 1000 as the sum.

For example purposes, we use an array just to operate on a large number of bytes. This makes the desired effect appear with a higher probability. However, the exact data type does not matter and the logic would be the same even if the array were a simple integer.

Let’s write the code for this:

// Producer creates the array, fills it with data, and stores it here.// Consumer loops until this is non-null, then processes contents of array.static ARRAY_PTR: AtomicPtr<[u8; ARRAY_SIZE]> = AtomicPtr::new(ptr::null_mut());let _producer = thread::spawn(|| { // The array starts with 0x00 values in every slot. let mut data = Box::new([0u8; ARRAY_SIZE]); // Then we fill it with 0x01 in every slot. for i in 0..ARRAY_SIZE { data[i] = 1; } // Then we publish this array for the Consumer to verify its contents. ARRAY_PTR.store(Box::into_raw(data), Ordering::Relaxed);});let mut ptr: *mut [u8; ARRAY_SIZE];// Wait for array to be published by Producer.loop { ptr = ARRAY_PTR.load(Ordering::Relaxed); if !ptr.is_null() { break; }}let array: &[u8; ARRAY_SIZE] = unsafe { &*ptr };// If every field is 0x01, the sum will be ARRAY_SIZE.let sum: usize = array.iter().map(|b| *b as usize).sum();if sum != ARRAY_SIZE { println!("Observed anomalous sum: {} x 1 == {}", ARRAY_SIZE, sum);}The code already avoids one mistake by storing the published pointer in an atomic variable of type AtomicPtr. The reason is the same as it was in the first problem – data being accessed simultaneously from multiple threads requires the use of atomic variables for correctness, guaranteed by the atomicity property of atomic variables. It does not matter that Producer only writes and Consumer only reads – read access matters just as much as write access. We can skip atomic variables for concurrently accessed data only if all access is via shared references. Of course, the Rust language would also do its best to stop us if we tried to skip using atomic variables (e.g. by not allowing us to create both a &mut exclusive reference and a & shared reference to the same variable).

It is important to explore the difference here between the pointer to the array and contents of the array – why do we not need atomic variables for the data inside the array (i.e. why is it not an [AtomicU8; 1000])?

This is because while the array contents are indeed also being accessed by two threads, they are not being accessed by them at the same time – Producer only accesses the contents before it publishes the array and Consumer only accesses the contents after it has received the published array. In the conceptual sequence of operations there is no overlap in time when both Producer and Consumer are accessing the array, so we are not required to use atomic variables for this data.

In our example, we will repeat this validation logic a large number of iterations to ensure that we detect even anomalies that happen with a very small probability. Recall the “one in 10 000 servers crashes per day” scenario described earlier – that is a very low occurrence of an issue considering the systems would each be handling tens of thousands of concurrent sessions. In our example, we want to be extra certain we detect even a 0.0001% probability fault – multithreaded logic requires extreme thoroughness from us because it can introduce subtle errors with large consequences. This is not typically done for real-world test code, though can still be a valuable technique under some conditions (especially when combined with Miri).

const ITERATIONS: usize = 1; // Miri is slow, one is enough under Miri.const ITERATIONS: usize = 250_000;println!("This may take a few minutes. Please wait...");for i in 0..ITERATIONS { let consumer = thread::spawn(|| { // ... if sum != ARRAY_SIZE { println!("Observed anomalous sum: {} x 1 == {}", ARRAY_SIZE, sum); return ControlFlow::Break(()); } else { // Sum is correct. Try again. // We leak the memory to ensure each iteration uses a different memory address. ARRAY_PTR.store(ptr::null_mut(), Ordering::Relaxed); return ControlFlow::Continue(()); } }); match consumer.join().unwrap() { ControlFlow::Break(()) => { println!("Anomaly was detected on iteration {}/{ITERATIONS}.", i + 1); return; } ControlFlow::Continue(()) => {} }}println!("No anomalies observed after {} iterations.", ITERATIONS);Let’s review the logic: on one thread, we create an array, then publish it; on the other thread, we wait for the array to be published, then consume it. Seems sound, right? What could possibly go wrong? Let’s run it on a typical x64 system.

cargo run --example 03_array_passing --release --quiet

This may take a few minutes. Please wait...

No anomalies observed after 250000 iterations.

It works! Phew, it would have been scary to see that very straightforward logic fail.

Let’s also try this program on an ARM system, just because we have one available.

cargo run --example 03_array_passing --release --quiet

This may take a few minutes. Please wait...

Observed anomalous sum: 1000 x 1 == 936

Anomaly was detected on iteration 1879/250000.

Oh no!

There is valid and there is valid

A program is valid if it satisfies the rules of the programming language. These rules are different from the rules imposed by the hardware. One reason for this is that programming languages tend to support multiple hardware platforms with different sets of rules.

This means that an invalid program may still do “the right thing” if:

- The compiler does not transform the logic in surprising ways (which it is often allowed to do).

- The program satisfies the rules of the hardware it runs on.

This explains why we saw a successful result on the x64 system – both factors were in our favor there.

The array sharing program we wrote is invalid Rust code because it contains a programming error in the form of a data race. A data race is undefined behavior and the compiler is allowed to do whatever it wants in case of undefined behavior – from pretending everything is fine, to removing the offending code, to inserting a crypto miner, to taking out a bank loan in our name. We got lucky in our case because the compiler decided not to apply any unwanted transformations that would break our code completely.

The x64 platform is quite forgiving with its multithreading rules, so the program still worked correctly on the x64 system and from the point of view of the hardware, everything was fine. From the programmer’s point of view, the hardware did exactly what we expected from it despite the code being invalid from a programming language point of view.

The ARM platform is much less forgiving and invalid code has a lower probability of working correctly on ARM. Around 0.002% of the time our program will fail on the ARM system the author used for testing, though this will greatly depend on the specific hardware and the exact code being executed.

This lower tolerance for mistakes makes it valuable to test low-level multithreading logic on ARM processors.

In any case, the data race is immediately and consistently detected by Miri because Miri validates behavior against the rules of the programming language, not the hardware platform.

MIRIFLAGS=”-Zmiri-ignore-leaks”

cargo +nightly miri run --example 03_array_passing

error: Undefined Behavior: Data race detected between (1) retag write on thread `unnamed-2` and (2) retag read of type `[u8; 1000]` on thread `unnamed-1` at alloc3323

--> examples\03_array_passing.rs:52:53

|

52 | let array: &[u8; ARRAY_SIZE] = unsafe { &*ptr };

| ^^^^^ (2) just happened here

|

help: and (1) occurred earlier here

--> examples\03_array_passing.rs:38:33

|

38 | ARRAY_PTR.store(Box::into_raw(data), Ordering::Relaxed);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

= help: retags occur on all (re)borrows and as well as when references are copied or moved

= help: retags permit optimizations that insert speculative reads or writes

= help: therefore from the perspective of data races, a retag has the same implications as a read or write

= help: this indicates a bug in the program: it performed an invalid operation, and caused Undefined Behavior

= help: see https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/reference/behavior-considered-undefined.html for further information

= note: this is on thread `unnamed-1`

note: the current function got called indirectly due to this code

--> examples\03_array_passing.rs:25:24

|

25 | let consumer = thread::spawn(|| {

| ________________________^

26 | | // We start Producer here, to ensure that Consumer starts first.

27 | | // This increases the probability of seeing the desired effects.

28 | | let _producer = thread::spawn(|| {

... |

66 | | });

| |__________^

We must explicitly disable the Miri memory leak detector here via the MIRIFLAGS environment variable because our example intentionally leaks memory to ensure that every iteration runs with a unique memory address, which is a realistic memory access pattern that makes it easier to reproduce the issue.

Where is the data race?

It is a fact that the example fails on ARM hardware but it is less obvious why. The error messages from Miri are often only the first step in an investigation and rarely reveal the whole picture. Let’s explore the factors involved.

It is common to think of code execution as a linear process. Take the array publishing on the Producer thread, for example:

// The array starts with 0x00 values in every slot.let mut data = Box::new([0u8; ARRAY_SIZE]);// Then we fill it with 0x01 in every slot.for i in 0..ARRAY_SIZE { data[i] = 1;}// Then we publish this array for the Consumer to verify its contents.ARRAY_PTR.store(Box::into_raw(data), Ordering::Relaxed);A very typical way to reason about this code would be:

- A new array is created.

- After creating the array, it is filled with

0x01bytes. - After filling the array, the pointer to it is published.

This is true but only in a certain sense. It is true only locally – within one thread! And it is true only in the abstract.

This is why in the earlier description of the example some specific phrasing was used:

In the conceptual sequence of operations there is no overlap in time when both Producer and Consumer are accessing the array [..].

This is certainly what we would want to be the case. However, the code we wrote actually defines a different sequence of operations! The reality is that programming languages present us with a very simplified view over what happens in the hardware. As we break through the layers of abstraction, we find many factors that can shatter this illusion.

First, we must consider how the compiler sees our code. It is allowed to reorder operations in code if it thinks a different order is more optimal. It is allowed to do this as long as the end result remains the same (i.e. as long as no dependencies between operations are violated). What are the dependencies in our array publishing code? Let’s examine it from bottom to top:

- The pointer to the array is published to a shared variable.

- Before the pointer can be published, the array we are pointing to must be created.

- The array is filled with

0x01bytes. Obviously, the array must be created before it can be filled.

But what about a relationship between filling the array with 0x01 and publishing the pointer to the array? Our code does not define any relationship between these two. Filling the array and publishing the pointer are independent operations as far as the compiler is concerned. It is entirely legal for the compiler to decide to fill the array with 0x01 after publishing the pointer! The mere fact of us writing the “fill with 0x01” code before the “publish pointer” code does not establish a dependency between these operations.

Some exploration of the compiled machine code of this example indicates that we got lucky and the compiler did not make any reordering transformations. This is true at time of writing and such behavior may change with compiler versions. This luck is part of the reason the code works on the x64 processor architecture. If a future version of the compiler decides to reorder the operations here, the code might also break on x64 systems. This is our first hint that in valid multithreaded code, we must sometimes explicitly define dependencies between operations if we want X to occur before Y. We will cover how to do this in the next chapter.

This was just about what the compiler does. Even if the compiler does not reorder anything, we need to consider what the hardware does when it executes the code. The hardware is not at all linear in its behavior. A modern processor performs many operations simultaneously, even speculating about future choices that are not yet known.

Again, there is the underlying principle that the hardware is allowed to do this as long as the end result remains the same under the ruleset of the hardware architecture. Does the hardware consider there to be any dependency between the filling of the array with 0x01 and the publishing of the pointer?

There are different kinds of relationships and dependencies that need to be considered when dealing with hardware but if we greatly simply things we could say:

- For x64, yes, a dependency exists between the “fill with

0x01” and “publish pointer” - For ARM, no, the operations “fill with

0x01” and “publish pointer” are independent.

The impact of this is that on ARM, the published pointer can sometimes be observed by the Consumer thread before the array has been filled with 0x01 values. Even if the code on the Producer thread filled the array before publishing the pointer!

Ultimately, the “why does it happen” does not really matter – the hardware architecture ruleset allows it to happen and there may be multiple different mechanisms in the hardware itself that can yield such a result (e.g. perhaps the pointer publishing and 0x01 fill are literally executed at the same time by different parts of the processor, or perhaps the 0x01 fill does happen first but the updated memory contents are simply not published to other processors immediately).

The good news is that as long as we follow the Rust language ruleset, we are guaranteed to be compatible with all the hardware architectures that Rust targets – we only need to concern ourselves with what Rust expects. All this talk of hardware architectures is just here to help understand why the Rust language rules exist.

To fix both aspects of the data race (to prevent compiler reordering and to ensure that the Consumer thread sees the right order of operations) we need to signal to both the compiler and the hardware that a dependency exists between publishing the pointer and filling the array.

Establishing the missing data dependency

We have determined that a data race exists between the writing of the 0x01 values on the Producer thread and the reading of the array contents on the Consumer thread. Let’s fix it by adding the missing data dependency, which makes the code valid Rust code and automatically implies that the hardware will do what Rusts expects it to do (and what we expect it to do) regardless of the hardware architecture.

Defining the data dependency requires two changes.

First, we must tell the compiler that publishing the pointer to the array depends on first executing all the code that came before it (the writing of the 0x01 values). We do this by signaling the Release memory ordering:

// The array starts with 0x00 values in every slot.let mut data = Box::new([0u8; ARRAY_SIZE]);// Then we fill it with 0x01 in every slot.for i in 0..ARRAY_SIZE { data[i] = 1;}// Then we publish this array for the Consumer to verify its contents.ARRAY_PTR.store(Box::into_raw(data), Ordering::Release);The names of the memory ordering modes are rather confusing. Do not read too much into the names – they are still confusing and low-signal to the author even after years of working with them.

Release ordering means “this operation depends on all the operations that came before it on the same thread”.

For the compiler itself, defining a Release memory ordering may often be sufficient because it establishes the dependencies between operations and prevents problematic reordering by the compiler.

However, this is not enough to establish the data dependency for the hardware that executes our code!

When considering what the hardware does it is more useful to think of Release ordering as merely metadata attached to the actual data written. It does not necessarily change what the hardware does when executing the write operation but merely sets up the first stage of a transaction.

To actually “close the loop” here and complete the transaction, we need to also instruct the hardware to pay attention to these metadata declarations when reading the data. We do this by using the Acquire memory ordering. Acquire ordering means “if the value was written with Release ordering, make sure we also see everything the originating thread wrote before writing this value”.

let mut ptr: *mut [u8; ARRAY_SIZE];// Wait for array to be published by Producer.loop { ptr = ARRAY_PTR.load(Ordering::Acquire); if !ptr.is_null() { break; }}How exactly the hardware does all of that is hardware-implementation-defined but you can think of Acquire as a “wait for all the data we depend on to arrive” instruction. Yes, literally – an Acquire memory ordering can make the processor just stop executing any code until the data has arrived!

This reinforces the fact that atomic variables are slow. This synchronization takes time and effort from the hardware and is not free. While still cheaper than heavyweight primitives like mutexes, atomic variables are still costly compared to regular memory accesses and code aiming to be highly scalable on systems with many processors should minimize any synchronization logic, even logic based only on atomic variables.

Dependencies between operations can be difficult to reason about, so to help understand what just happened, we can take the original diagram that introduced this example and annotate it with the dependency relationships that ensure steps 1, 2, 3 and 4 actually occur in that order from the point of view of all relevant participants.

- Starting from the back, the dependency between steps 3 and 4 is guaranteed by the Rust language – we simply cannot read the array until we have a pointer to the array.

- The dependency between steps 2 and 3 is guaranteed by using

AtomicPtr, which makes the pointer (in isolation) valid to operate on from multiple threads (and obviously, we cannot read a non-null value from it before there is a non-null value in it). - The dependency between steps 1 and 2 is the one that this whole chapter has been about. Without memory ordering constraints, this dependency would not exist and step 1 might come after step 2.

The combination of Release and Acquire on the write and read operation is what solves the data race by creating the data dependency:

- The write with

Releaseordering establishes the dependency on the Producer thread. - The read with

Acquireordering “spreads” that dependency into the Consumer thread.

Now both the compiler and the hardware know about the relationship between the data and they can each take proper care. Let’s run it again on ARM:

cargo run --example 04_array_passing_fixed --release --quiet

This may take a few minutes. Please wait...

No anomalies observed after 250000 iterations.

A clean pass! Running Miri on the fixed version also gives us a clean bill of health.

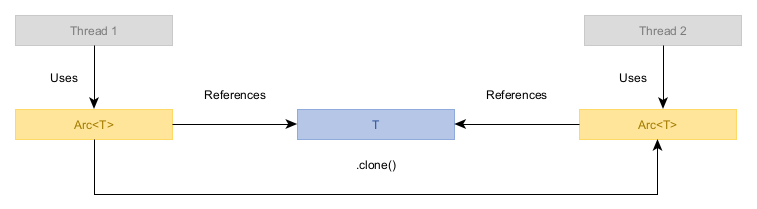

Case study: Arc

To reinforce the concepts described above, let’s look at how one might implement a reference-counting smart pointer like Arc, whereby a value is owned by any number of clones of the smart pointer, with the last one cleaning up the value when it is dropped.

The usage should look something like the following:

let x = Arc::new(42);println!("Value: {:?}", *x);let thread_two = thread::spawn({ let x = x.clone(); move || { println!("Thread Two Value: {}", *x); }});let thread_three = thread::spawn({ let x = x.clone(); move || { println!("Thread Three Value: {}", *x); }});thread_two.join().unwrap();thread_three.join().unwrap();A simple implementation of Arc consists of:

- The owned value of type

T, shared between all clones of theArc. - A shared reference count, indicating how many clones exist. When this becomes zero, the value is dropped.

We will put this shared state into a struct and make cloneable smart pointers, each pointing to this data structure.

struct SharedState<T> { value: T, ref_count: usize,}struct Arc<T> { ptr: NonNull<SharedState<T>>,}impl<T> Deref for Arc<T> { type Target = T; fn deref(&self) -> &Self::Target { unsafe { &self.ptr.as_ref().value } }}Before we go further with the implementation, let’s analyze the design based on what we have covered earlier in this article.

Do we need to use atomic variables? Recall that atomic variables are needed if multiple threads concurrently access the same variable and at least one of the threads performs writes.

We can consider the owned T as read-only for concurrent use because our Arc never modifies it and only returns shared references that do not allow mutation of the value. When mutation does occur (dropping the T) we are guaranteed that only one thread is operating on the variable because only the last clone of the Arc can drop the T – if a drop is happening, no other threads could remain to access it.

This means there is no need to involve atomic variables in the storage of T. This is good because there is no general purpose Atomic<T> type – atomic variables only exist for primitive types and our T could be anything. Indeed, one principle of synchronization logic is that concurrent writable access is only possible on primitive data types and alternative approaches like mutual exclusion must be used for complex types.

Conversely, the reference count will be modified by every clone of the Arc, so it must be an atomic variable (e.g. AtomicUsize).

struct SharedState<T: Send> { value: T, // Immutable until drop, read-only via shared references. ref_count: AtomicUsize, // Mutated by all clones of the Arc.}Do we need to care about memory ordering? Recall that memory ordering is relevant if there are multiple variables involved in multithreaded operations.

This one is not so easy to assess correctly. At first glance, one might say that only the shared reference count is related to any multithreaded operations – after all, the owned value T is read-only (Arc does not return &mut exclusive references so a & shared reference is the most you can get) until it is dropped, which happens in a single-threaded context. However, this line of reasoning is flawed.

The error in our thinking is that a Rust object is not necessarily read-only even if all you have is a shared & reference to it! You do not need a &mut exclusive reference to mutate an object – the type T may still be internally mutable! It may have fields containing Mutex<U>, atomic variables or other data types that do not require an exclusive reference to mutate. While for the “do we need to use an atomic variable” assessment, this did not matter (it is handled by the type T internally), it does matter for data dependency considerations.

This means there are, in fact, two potentially changing variables involved – the T and the reference count.

Still, this is not an answer to the original question. We also need to determine whether these two variables are dependent or independent. Does a data dependency exist that we need to signal to the compiler and the hardware? We must consider the full lifecycle of each value here. The key factor is that the last Arc clone must drop the instance of T after decrementing the reference count to zero.

The word “after” is the dependency we are seeking – dropping an object requires the drop logic to access the data inside that object and we need to ensure that the drop logic sees the “final” version of the T, after all changes from other threads have become visible (i.e. after seeing all the writes made by all the other threads before they dropped an Arc clone).

In other words, the drop of the T can only occur as the last operation in the lifecycle of T. Sounds obvious when put that way but this does not happen automatically in multithreaded logic.

To make it happen, we need to impose memory ordering constraints in Arc to signal the data dependency from the reference count to the T:

- When a clone of the

Arcis dropped, the reference count decrement is performed withReleaseordering to signal that any writes intoTon this thread must be visible before the decrement becomes visible on other threads. - When a clone of the

Arcis dropped, the reference count decrement is performed withAcquireordering to ensure that (if it decrements to zero and we need to drop theT) we see all changes that happened on other threads before they decremented their own reference count.

That’s right, the same operation needs both Release and Acquire memory ordering semantics. This is one of the standard memory ordering constraints, Ordering::AcqRel.

impl<T: Send> Drop for Arc<T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let state = unsafe { self.ptr.as_ref() }; if state.ref_count.fetch_sub(1, Ordering::AcqRel) == 1 { // The previous value was 1 so now we are at 0 references remaining. unsafe { drop(Box::from_raw(self.ptr.as_ptr())); } } }}impl<T: Send> Clone for Arc<T> { fn clone(&self) -> Self { let state = unsafe { self.ptr.as_ref() }; state.ref_count.fetch_add(1, Ordering::Relaxed); Self { ptr: self.ptr.clone(), } }}Note that we only care about decrementing the reference count and not incrementing it. This is because we have no dependency on the value of T when incrementing the reference count as it is the dropping of the T after the last decrement that involves a data dependency. This means that incrementing the reference count can use Relaxed ordering because Arc clones on different threads do not care about any writes into T that occur if T is not being dropped.

To be clear, the type T might certainly care about writes into the T being synchronized between threads but if so, it can define its own memory ordering constraints in its own mutation logic.

cargo run --example 05_arc --release --quiet

Value: 42

Thread Two Value: 42

Thread Three Value: 42

cargo +nightly miri run --example 05_arc

Value: 42

Thread Two Value: 42

Thread Three Value: 42

That works. Miri does not complain. We have created a functional Arc!

Strengthening an operation after the fact

The Arc we created in the previous chapter is suboptimal because it always performs the reference count decrement with Acquire+Release ordering. The problem is that the Acquire part is only relevant for us if the reference count becomes zero – if we are not going to drop the T, there is no need to ensure we have visibility over the writes from other threads.

Recall that an Acquire memory ordering constraint is a “stop and wait for the data to become available” command to the hardware – we are potentially paying a price on every decrement!

There is a solution to this, though:

- First, we perform the decrement with only

Releaseordering. - Then we check if the reference count became zero – if not, we do nothing.

- If it did become zero, we define an

Acquirefence. - Finally we drop the

T.

A fence is a synchronization primitive used to “strengthen” the previous operation on an atomic variable, allowing us to only pay for the Acquire ordering constraint when we need it. It works exactly as if we had written the ordering constraint on the previous atomic variable operation (the reference count decrement) but allows the effect to be conditionally applied at a later point in time and code.

impl<T: Send> Drop for Arc<T> { fn drop(&mut self) { let state = unsafe { self.ptr.as_ref() }; if state.ref_count.fetch_sub(1, Ordering::Release) == 1 { // The previous value was 1 so now we are at 0 references remaining. fence(Ordering::Acquire); unsafe { drop(Box::from_raw(self.ptr.as_ptr())); } } }}This code is functionally equivalent but simply more efficient. The size of the effect depends on the hardware architecture and may be zero on some architectures.

Leave safety comments and document memory ordering constraints

The examples in this article made use of the unsafe keyword to lower the guardrails of the compiler so that we could do something risky. To keep the examples short and to the point, we committed a sin: we failed to provide safety comments for these unsafe blocks.

Safety comments are critical to writing maintainable unsafe Rust code. They are one half of a challenge-response pair:

- The API documentation of an

unsafe fndefines safety requirements that callers must uphold – this is the challenge. - The safety comment at the call site documents how the code upholds these safety requirements – this is the response to the challenge.

pub fn increase_shareholder_value(beans: &[u8]) { assert!(!beans.contains(&0x00)); // SAFETY: We asserted above that no 0x00 bytes are present. unsafe { jeopardize_the_beans(beans); }}/// # Safety////// The provided slice of bytes must not contain any bytes with the value 0x00.pub unsafe fn jeopardize_the_beans(beans: &[u8]) { // ...}Very often, errors in unsafe Rust code can be discovered when writing safety comments, as the act of writing down how exactly we uphold the requirements can lead to a realization that we are not actually meeting the requirements. Even after being written, safety comments are invaluable to reviewers and future maintainers, including AI agents that tend to be easily confused by unsafe Rust.

Safety comments should be considered mandatory for all unsafe Rust code. Every unsafe function call must be accompanied by a safety comment that describes how we uphold the safety requirements. Unsafe code without safety comments is not reviewable and not maintainable. It is normal and expected that safety comments make up a significant bulk of the source code in unsafe Rust.

Be extremely careful about AI-generated safety comments, though. They are often “SAFETY: All is well, this is valid, trust me bro” in nature and fail to adequately describe how the safety requirements of the function being called are upheld. Very often the AI does not even make an attempt to read the safety requirements of the functions being called, so the safety comments it makes can be completely off-topic hand-waving.

Similarly to safety comments, it is good practice to accompany atomic operations with comments that explain why the memory ordering constraint specified is the correct memory ordering constraint to use.

Memory ordering constraint logic can be very difficult to reverse-engineer and validate manually, so for the sanity of future maintainers and the success of future AI modifications, you should leave a comment on every operation on an atomic variable.

In a production-grade Arc implementation we would expect to see detailed safety and synchronization logic comments similar to the following:

impl<T: Send> Drop for Arc<T> { fn drop(&mut self) { // SAFETY: The state was created in Arc::new and is valid as long as // there is at least one Arc instance pointing to it. We never create // &mut exclusive references to it so it is always valid to create a // & shared reference to it. let state = unsafe { self.ptr.as_ref() }; // When a clone of the Arc is dropped, the reference count decrement // is performed with Release ordering to signal that any writes into // T on this thread must be visible before the decrement becomes // visible on other threads. if state.ref_count.fetch_sub(1, Ordering::Release) == 1 { // The previous value was 1 so now we are at 0 references remaining. // When a clone of the Arc is dropped and we have verified that the // reference count became zero, we apply a fence with Acquire // ordering to ensure that we see all changes that happened on // other threads before they decremented their own reference count // (i.e. we are dropping the final version of the value of type T). fence(Ordering::Acquire); // SAFETY: This pointer was allocated by Box::into_raw in Arc::new // and we have verified that the reference count is now zero, so // it is safe to deallocate it here - nobody else can use it again. // We no longer reference the "state" variable after this point, // ensuring that this function does not attempt to reference this data. unsafe { drop(Box::from_raw(self.ptr.as_ptr())); } } }}impl<T: Send> Clone for Arc<T> { fn clone(&self) -> Self { // SAFETY: The state was created in Arc::new and is valid as long as // there is at least one Arc instance pointing to it. We never create // &mut exclusive references to it so it is always valid to create a // & shared reference to it. let state = unsafe { self.ptr.as_ref() }; // The data dependency between the reference count and the inner value of // type T only exists when dropping the object of type T, so we do not // need to define any ordering constraints when incrementing the reference // count because an increment cannot result in a drop of the inner value. state.ref_count.fetch_add(1, Ordering::Relaxed); Self { ptr: self.ptr.clone(), } }}References

https://github.com/sandersaares/order-in-memory

The terminology makes much more sense if one thinks of the array as being initially locked. Then, the lock is released from the thread that initialises the array, and acquired from the thread that actually processes them.

LikeLike