Most production code is written without its performance being a goal, using “typical” coding patterns for different languages. These patterns tend to be exemplified in articles, official documentation and tutorials. Typical code allows you to get things done rapidly by making use of powerful and flexible language features and APIs. However, typical code is not always the fastest code.

There is one rule of thumb that I have found widely applicable for massive performance gains: get rid of memory allocation!

This is beneficial not only because memory allocation or garbage collection are inherently slow (compared to not doing either) but also because when transforming code to allocate less memory we are often forced to transform the code to a shape that is more efficient for other reasons such as reducing indirection in memory accesses, enabling more compiler optimizations and keeping buffers small and in the CPU cache. Often this requires us to step outside “typical” coding patterns.

In this article I will share a simple step by step example of how we can take a naively written C# function and greatly improve its performance by reducing how much memory it allocates. C# was chosen because its toolchain offers excellent benchmarking and memory analysis capabilities – I have successfully applied this technique to C++ and Rust code with similar results.

Scenario

An asynchronous function receives the 1000 first digits of Pi and outputs a censored version, where digits are replaced with ‘*’ if they are smaller than the previous digit, ignoring the starting “3”. The output is written to a Stream as UTF-8 bytes.

Example input: 3.1415926535897932384626433

Example output: 3.14*59*6**589*9**38*6*6**3

Typical C# implementation

This function implements the above scenario. It is written in typical C# style such as you might find in online tutorials and official documentation examples, using common string manipulation operations and LINQ data transformations.

public static async Task<int> WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesAsync(

string π, Stream output, CancellationToken cancel)

{

var components = π.Split('.');

var prefix = components[0];

var suffix = components[1];

var censoredNumberCount = 0;

char previous = '0';

var censoredSuffixChars = suffix.Select(c =>

{

var isSmallerThanPrevious = c < previous;

previous = c;

if (isSmallerThanPrevious)

{

censoredNumberCount++;

return '*';

}

return c;

}).ToArray();

var result = $"{prefix}.{new string(censoredSuffixChars)}";

await output.WriteAsync(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(result), cancel);

return censoredNumberCount;

}

How much memory is allocated?

Go ahead and try count each memory allocation in the above code. How many objects are allocated?

Reveal answer

The typical implementation allocates 13 objects on every call, and 1 additional object if the call to WriteAsync() needs to complete asynchronously.

The memory allocations are:

- The

Task<int>that is ultimately returned by the function. - The

string[]returned byπ.Split(). - The first string returned by

π.Split(), containing the characters before the dot. - The second string returned by

π.Split(), containing the characters after the dot. - The

char[]returned bysuffix.Select().ToArray(), containing the censored characters. - The closure used by the

.Select()lambda expression to capture thecensoredNumberCountandpreviousvariables. - The delegate used to pass the lambda expression to

Select(). - A

char[][]used internally by theSelect().ToArray()chain. - An iterator used internally by the

Select().ToArray()chain. - The

char-enumerator used by theSelect().ToArray()chain to obtain all the characters. - A temporary string to transform the censored characters into a string.

- The

resultstring with the final form of the censored Pi. - The

byte[]with the UTF-8 bytes of theresultstring. - (Only if

WriteAsync()completes asynchronously) A state machine box used to later continue the asynchronous function.

These memory allocations were identified via .NET memory tracing using the dotnet-trace tool.

That is a lot! Let’s transform this function to reduce memory allocation and see what changes.

See WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesAsyncAnnotated() for a reference of which line allocates which objects.

Transformation 1: we know Pi starts with 3

Let’s get the easy stuff out of the way first. The code performs some work that is clearly avoidable: we know that pi starts with “3.” and we have no need to process this part of the input string. Furthermore, we do not need to split the digits after the dot into a separate string because we know the “3.” prefix is always 2 characters long. Therefore, we can get rid of the string.Split() call and just operate on the digits after the dot.

// OPTIMIZATION: Operate on the chars from the original string,

// just skipping the "3." at the start.

var censoredSuffixChars = π.Skip(2).Select(c =>

{

...

}).ToArray();

// OPTIMIZATION: Just write the "3." prefix as a constant value.

var result = $"3.{new string(censoredSuffixChars)}";

await output.WriteAsync(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(result), cancel);

This saves 3 memory allocations:

- The

string[]returned fromstring.Split(). - The first string returned by

π.Split(), containing the characters before the dot. - The second string returned by

π.Split(), containing the characters after the dot.

See WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesOptimized1Async() on GitHub for full code.

Transformation 2: do not use LINQ

Many of the memory allocations in the list above were caused, either directly or indirectly, by the LINQ call chain π.Select(...).ToArray(). This is fairly typical of LINQ – it is a highly flexible tool that allows you to easily express complex transformations but often sacrifices performance to gain this flexibility. There are no two ways about it – we must get rid of LINQ in our function.

// OPTIMIZATION: Do not use LINQ, iterate the chars

// directly to construct the censored suffix.

var censoredSuffixChars = new char[π.Length - 2];

for (var i = 0; i < censoredSuffixChars.Length; i++)

{

var c = π[i + 2];

var isSmallerThanPrevious = c < previous;

previous = c;

if (isSmallerThanPrevious)

{

censoredNumberCount++;

censoredSuffixChars[i] = '*';

}

else

{

censoredSuffixChars[i] = c;

}

}

This saves 5 memory allocations:

- The closure that captured the

censoredNumberCountandpreviousvariables. - The delegate that was used to pass the lambda expression to

Select(). - The

char[][]allocated internally by theSelect().ToArray()chain. - The iterator allocated internally by the

Select().ToArray()chain. - The

char-enumerator allocated to access the characters of the input string.

See WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesOptimized2Async() on GitHub.

Transformation 3: do not use wasteful .NET APIs

.NET Framework was first released in 2002 and its base class library was clearly designed in the belief that allocating memory is cheap and affordable. Many .NET APIs are very profligate about allocating objects left and right.

It was not until 2018 that .NET Core 2.1 started adding more efficient APIs to the base class library, with the introduction of the Span and Memory types. Many tutorials, training videos and documentation examples today still use the old APIs that allocate memory when more optimal APIs are available.

Today, most .NET base class library APIs offer allocation-free alternatives. In our example code, one such case is Encoding.GetBytes(), which offers two variants of interest:

- The above code uses GetBytes(String), which allocates a new buffer for returning the encoded bytes.

- There also exists GetBytes(ReadOnlySpan<char>, Span<byte>) which accepts a

Spanas input, allowing the caller to provide a reusable buffer for the encoded bytes.

The next transformation changes the code to use a reusable buffer from the .NET array pool.

var result = $"3.{new string(censoredSuffixChars)}";

// OPTIMIZATION: Do not allocate memory when

// encoding the string to UTF-8 bytes.

var desiredBufferLength = Encoding.UTF8.GetMaxByteCount(result.Length);

var buffer = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(desiredBufferLength);

try

{

var usedBufferBytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(result, buffer);

await output.WriteAsync(buffer.AsMemory(..usedBufferBytes), cancel);

}

finally

{

ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Return(buffer);

}

This saves 1 memory allocation:

- The

byte[]for the UTF-8 encoded bytes.

See WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesOptimized3Async() on GitHub.

We could also use a pooled array for the char[] used to hold the censored characters. A larger transformation of the logic in the next step would make that obsolete, so it is skipped.

Transformation 4: operate on bytes

We know that the input string here is Pi, which only consists of ASCII alphanumeric characters. Therefore, we can simplify the algorithm by switching around the order of operations: first convert everything to UTF-8 bytes (which are a superset of ASCII) and then perform the censorship on the bytes directly – a single buffer contains all the hot data for the entire operation.

This entirely removes the need to keep two buffers – one for the characters and one for the bytes. Even reusable buffer allocations have some overhead, so the less buffer space we use the better.

public static async Task<int> WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesOptimized4Async(

string π, Stream output, CancellationToken cancel)

{

// Immediately convert everything to UTF-8

// bytes to avoid string operations.

var desiredBufferLength = Encoding.UTF8.GetMaxByteCount(π.Length);

var buffer = ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Rent(desiredBufferLength);

try

{

var usedBufferBytes = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(π, buffer);

var suffix = buffer.AsMemory(2..usedBufferBytes);

var censoredNumberCount = CensorSuffixOptimized4(suffix);

var censored = buffer.AsMemory(0..usedBufferBytes);

await output.WriteAsync(censored, cancel);

return censoredNumberCount;

}

finally

{

ArrayPool<byte>.Shared.Return(buffer);

}

}

private static int CensorSuffixOptimized4(Memory<byte> suffix)

{

...

}

This saves 3 memory allocations:

- The

char[]holding the censored characters. - The string used to transform the censored characters back into a censored string.

- The string used to assemble the “3.” prefix with the censored suffix.

See WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesOptimized4Async() on GitHub.

Transformation 5: ValueTask when you can

.NET supports two types of return values from asynchronous functions: Task and ValueTask. The latter is optimized for cases where the operation typically completes synchronously, in which case it enables allocation-free operation.

When to use it is a complex topic but an approximate rule of thumb is: if all asynchronous methods you call return ValueTask, make your asynchronous method also return ValueTask.

In our case, the only asynchronous call we make is Stream.WriteAsync(), which indeed returns ValueTask. Therefore, we can make our function return ValueTask.

public static async ValueTask<int> WriteCensoredDigitsOfPiAsUtf8BytesAsync(

string π, Stream output, CancellationToken cancel)

{

...

}

This saves 1 memory allocation:

- The

Task<int>for the return value.

See BetterImplementation class on GitHub.

Comparison

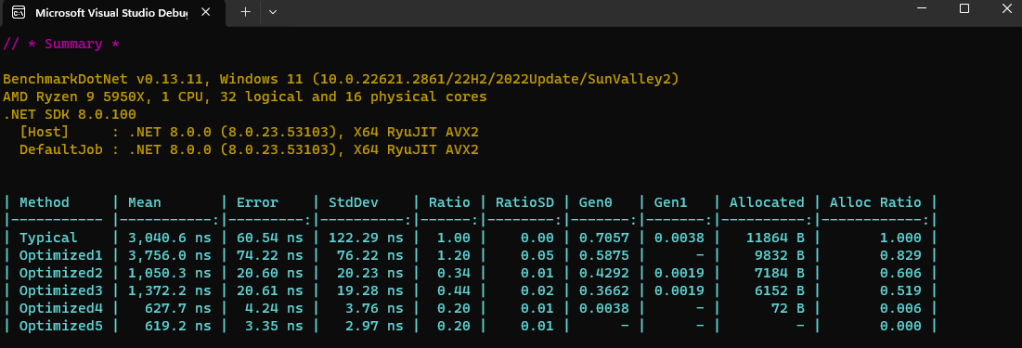

We have eliminated all 13 memory allocations! The code is now allocation-free, except for the case where output.WriteAsync() must complete asynchronously (in which case allocating a state machine box is unavoidable).

Does the code run faster now? Let’s break it down by each transformation.

| CPU cost | Memory cost | |

|---|---|---|

| Typical C# implementation | 100% | 100% |

| After transformation 1 | 120% | 83% |

| After transformation 2 | 34% | 61% |

| After transformation 3 | 44% | 52% |

| After transformation 4 | 20% | 1% |

| After transformation 5 | 20% | 0% |

Yes, we reduced the CPU time cost to 20% of the original – the function is now 5x faster!

Not every transformation of the code decreased the CPU cost – some increased it! This highlights the importance of measurements but also the importance of being persistent and not stopping when the first step does not bring desired results – big gains may require you to first go through steps that are not beneficial on their own, merely prerequisites for the final payoff.

What is the tradeoff?

In the “pi censorship” example above the code did not get significantly more complex in its optimized form. However, this is not always the case – writing more optimized code that allocates less memory often brings with it increased code verbosity, increased logic flow complexity and greater coupling.

| Typical implementation | Optimized implementation | |

|---|---|---|

| Lines of executable code | 15 | 21 |

| Cyclomatic complexity | 2 | 1 + 3 |

| Class coupling | 10 | 13 + 2 |

With experience, you can identify patterns that help bring the complexity under control but ultimately, in many cases you still end up expanding a one-line operation into 10 lines just to have greater control over the memory use.

Reproducing the results

The code is on GitHub: https://github.com/sandersaares/top-tips-for-csharp-optimization

Open the solution in Visual Studio, build using the Release configuration and run the app. Benchmark results will include both CPU and memory measurements.

[MemoryDiagnoser]

//[EventPipeProfiler(BenchmarkDotNet.Diagnosers.EventPipeProfile.GcVerbose)]

public class PiCensorship

{

To see specific objects being allocated, uncomment the EventPipeProfiler attribute in PiCensorship.cs, run the benchmarks and analyze the generated trace files with PerfView.

2 thoughts on “Memory allocation is the root of all evil”